The Llylgamyn Adventurers' Journal ~ A Wizardry Gaiden I Reflection

Despite my apprehensions about tackling one of the earliest, most decorated singleplayer RPG series in history, jumping into Wizardry Gaiden is a relatively simple affair – create some custom characters: choose their name, race, alignment, stats, and class; stick six compatible characters into a party; and buy (or not) some starting gear from the… disconcertingly extremely empty item shop; and equip all the gear you end up with. The idea of managing six blank-slate characters seemed a bit intimidating at first, but between having a little prior knowledge of the game and leaning on my friends as party members, I put together a team of six good friends with character specifications that they chose, and dove straight into the dungeon with very little hassle.

One of the first things I noticed after starting is that, while far from thoughtless, Wizardry Gaiden’s combat is relatively simple and snappy: there isn’t much to consider during individual encounters except for proper enemy targeting and managing spell uses on casters, so combat is largely a case of understanding which enemy types are the biggest threats and dealing with them as quickly as possible, while trying not to spend too many resources per fight. With smart target priority, most encounters – even bosses – can go down in a couple of turns with only minor losses, and though there’s a high miss chance on both ends, putting a lot of melee combat down to variance, turns resolve so quickly that combat feels breezy regardless of how many turns it takes. It means that depth from combat is almost purely attritional risk-management – how much can I reasonably spend on this fight? how far can I risk pushing into the dungeon with the resources I have? – rather than having depth of decision-making in individual encounters.

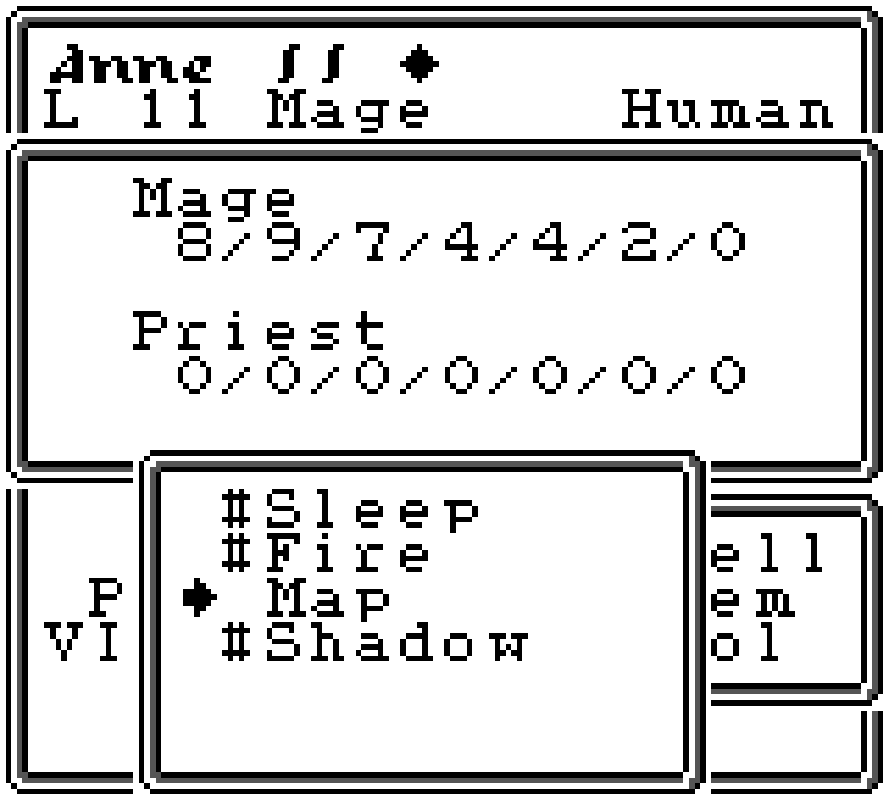

This isn’t a bad thing, though; rather, it establishes early on that combat is not the sole dimension of the dungeon crawl. A lot of time will rather be spent drawing maps: the in-game map spell is limited and sometimes impractical, so recording all possible information manually often feels necessary for recording information practically, and referencing and cross-referencing maps makes locating spatially-telegraphed secrets far, far easier. In a sense, while combat is the vessel for character progression, mapping effectively acts as a marker for dungeon progression, with the latter being just as important as the former for easing exploration. Each dead end bumped into, each hidden door discovered, each annoying teleport trap noted down, makes future dives much easier, as figuring out the exact shortest and safest path to move forward effectively reduces the amount of encounters fought as much as possible. And when combat, especially later on, can turn sour as quickly as it often does, avoiding as much combat as possible is often preferable to simply trying to muscle through it all.

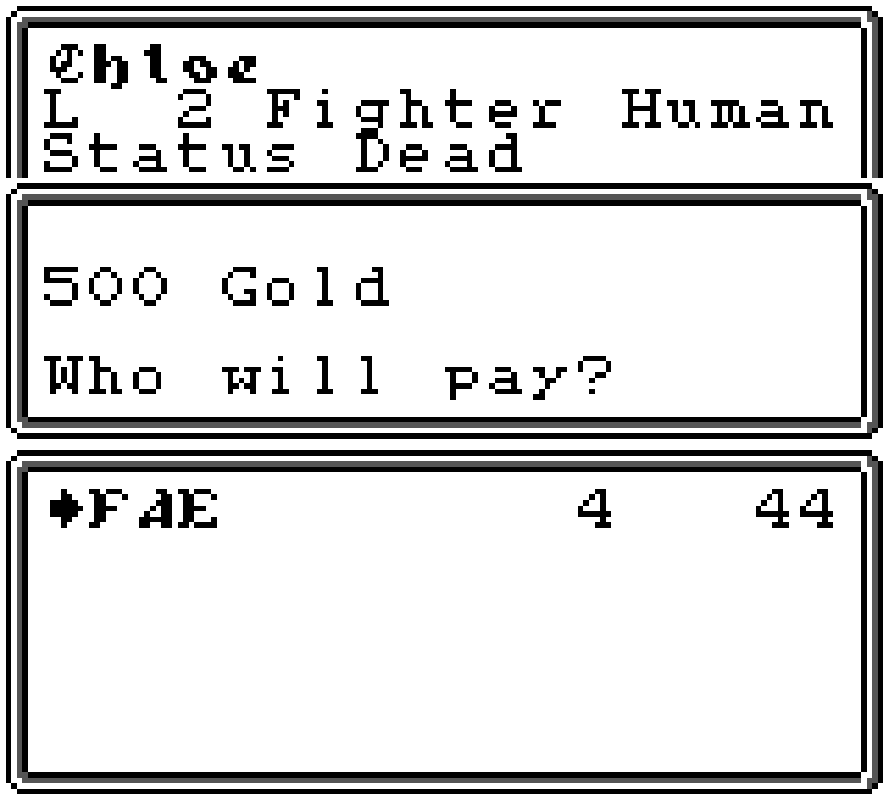

Of course, it won’t take long before being forced to run back to town, for one reason or another. Throughout a large chunk of the game, death and disabling statuses can only be healed at the town’s church – by paying a large sum that scales with the character's level. It’s frighteningly possible to be left without enough money to revive every lost party member – especially early on – since earning that money isn't easy: dropped items need to be identified before they can be sold, but doing so at the shop costs as much as their sell price – you're not making any profit, you're just stocking the shop's shelves. The only direct way to earn money is the loose change dropped by enemies, and encounters are surprisingly uncommon while walking around – only having a high chance when moving through doors. It makes intentionally grinding somewhat of an involved process: figuring out the most suitable grind spots in the dungeon – those with the highest density of doors, with the shortest route back to town – exploration, mapping and familiarity is an essential factor in every aspect of the crawl.

And as I kept delving, exploring, dying and returning, the game began to show its hand, a willingness to permanently throw a wrench in your strategies. It’s harshest in its attitude to character loss: revival has a small chance of failing, with the character being lost permanently if a second, more expensive revival, fails; and certain events within the dungeon can modify characters’ alignments, which can cause party members to become incompatible with each other. Both work to force important characters out of your party while being largely out of your control – and both happened to me multiple times throughout the game! But while it seems frustrating to lose a character in this way, it's equally surprisingly easy to bounce back: new party members can catch up safely if they're kept in the back row and trained by the rest of the party against stronger enemies, while adding new characters this way can afford experimentation with other options that might not have fit in the party originally. Misaligned characters aren’t permanently lost, and can be later brought back into a party if the other characters shift back to allow them. So, none of these losses are ultimately as bad as they sound, and it these tricks never feel intended as an outright punishment, rather as a language to add interesting and unexpected wrinkles to the adventure whilst, giving enough tools to comfortable meet it on its own terms – it’s expecting me to become more comfortable pushing through major setbacks, and maybe finding merit in it on the other side.

And fittingly so, I eventually dove a little bit too deep, made some poor panic decisions in a fight, and... my party was wiped out entirely. Rather than reverting to a previous save (the game autosaves very frequently), the fallen party remains in the dungeon and a new one has to go down to rescue them. This was a terrifying prospect at first – it'll be hours of grinding! it’ll take so long! – but it turned out to be the exact moment that made all the game’s meticulously-planted pieces fall into place. The shop, now stocked with all the old gear that was sold off for no profit throughout the game, allowed the new party a massive headstart via all the gold their [[ancestors]] had amassed. Levels had to be grinded up rather than earned organically through exploration, as the dungeon had already been explored, but my familiarity with the dungeon at that point made knowing and reaching the best grind spots quicker and easier than I could have imagined – dungeon-crawling muscle memory! – and a character who was forced to leave the first party due to an alignment conflict ended up leading the new blood, helping them grow and reach the old party even quicker than they could have by themselves. And as the dungeon was fully mapped already, the new party could charge straight down for the rescue as soon as they were strong enough! After the rescue mission, some of the new party had even managed grow stronger than the old, and I was able to combine the two to make a new party – a super team – who eventually made it through to the very end. What was initially a demoralising setback ultimately ended up making my party stronger than it would have ever been otherwise, and what frightened me as a massive, dissatisfying time-sink was the pivotal moment that made all the game’s mechanics and ideas come together, and what made its storytelling language abundantly clear.

I tend to talk a lot about the use of mechanics as storytelling in video game RPGs – after all, they’re all descendants of tabletop RPGs – but games like this, that are such a close interpretation of TTRPGs, land in a uniquely strange place: they’re modelled off functionally social games with a group dynamically shaping the game’s events; but as they lack said social aspect, singleplayer adaptations are left to convey that experience as well as possible purely through their mechanics being pushed against by input of a single player. Their resulting storytelling language is one that can lay down the potential for interesting situations to arise purely as the consequences of your play, but wants you to find intrigue in all its [[situations]] – even what might feel frustrating or undesirable – in order to get the most out of it, as those and their resulting outcomes are what ultimately form into the story of the game. So I suppose it shouldn’t be surprising that a Wizardry, of all games, managed to pull this off so sharply – every harsh setback harmonising with my own response to it, creating unique little stories that I can still look back on with fondness, even months later.

~*ʚїɞ*~

Thank you for reading, as always. This one’s been on the backburner for a long, long time, long enough to have started Gaiden III in the meantime…! I've been chipping away at this for months, to the point where I wasn't sure it was going to get finished, so I'm happy I got this pushed out just before the new year. I think the mechanical core of these games is really wonderful; I feel that RPG combat is very easy to execute wrong in a ‘slightly kind of dull’ way, and many of the post-DQ RPGs I’ve played feel like they live and die on combat and dungeons having a strong immediacy; these games push back in enough other ways to stay interesting even in the stretches where combat falls a bit flat. There’s so many often-unassuming moving parts in this, that I felt I had to dedicate so much space to just… talking about them! I hope it's not too unfocused.

As usual, if you like what I do and you’d like an easier way to follow it, you can subscribe to my Substack and get these beamed directly to your email box – it’s free and always will be. See you next time. ~♡