FINAL FANTASY II and Moving Backwards

I love Final Fantasy II. It’s an incredibly mood-driven dungeon-crawling affair with systems both as uneven as they are intensely satisfying to get to grips with, as they nudge your habits away from conventional RPG wisdom and push you towards unusual methods to twist and manipulate those systems in your favour. It’s infamously something of an outlier – as an RPG that challenges specific genre standards that’ve existed since Wizardry, and as a notable deviation in a popular, long-running series which would immediately pivot away from its new ideas. Those idiosyncrasies land at the forefront of discussion about its poor reputation – unusually poor, even for the modern-day standards of an experimental NES game – but much of what makes it maligned, or even just different, are the reasons it shines so brightly to me.

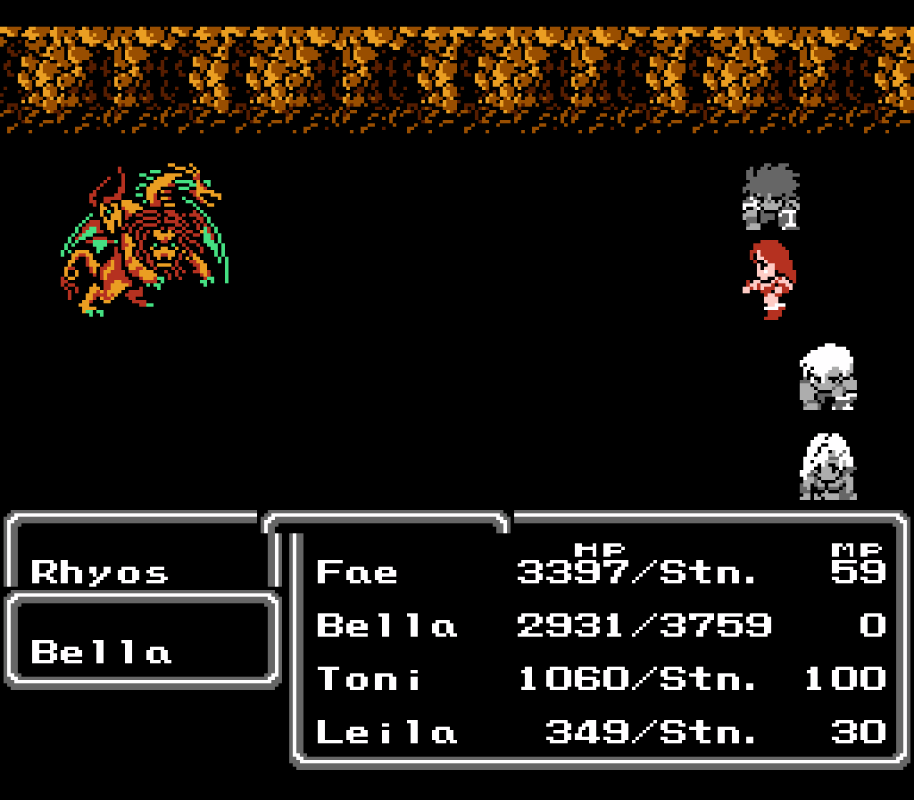

What sings to me the most is its clearest mechanical innovation – the action-based growth system, where stats grow through repeated action rather than via traditional levels. It’s interesting enough on the surface in how its freeform nature lets you fit each party member into any role you want – while the time-cost of weapon leveling is too high to reasonably role-switch mid-game, it allows the personal freedom to create hand-picked role combinations, like the star of my team: my highly-adaptible hybrid black-mage/white-mage archer. But the progression systems themselves are what make it so compelling, as a cursory knowledge of its particularities creates a slew of constant micro-decisions within each fight to try to optimise stat gains as much as possible. Should I intentionally tank through strong enemies without healing to encourage HP growths at the risk of dying, or should I be healing constantly to encourage Spirit and MP growths on my healers? Should I be using my low-level utility spells to level them for later, or do I need the MP and turns for more immediately-practical use? How much of this can I afford to do while preserving the resources I need to survive the dungeon? And how much of it can I squeeze out of each individual encounter when I’m in a safer area?

This extends to the popular perception of Final Fantasy II being a game where you beat up your own party to level – this is obviously silly both conceptually and as the grinding method it’s often purported as, but these seemingly-counterintuitive options add another layer to the growth optimisation game: while re-treading through safer areas, my party can hit each other during encounters to squeeze out extra HP growths and Cure casts without the usual risk of doing so, or cast contextually-useless spells to help level them up for when they’re needed. As there’s little or no extra time-cost to doing this when magic clears the groups in a single cast or entire encounters start running from you, it lets these weaker encounters give extra opportunity for growth as opposed to feeling like the speedbumps they often do. And there’s a further risk-reward aspect to this from how dungeons like to intersperse very weak and very strong encounters: should I be going for these costly stat optimisations against the weaker encounters, or should I save my resources to survive the really dangerous ones? It’s an unintuitive system in some ways, obviously – even if it's not strictly necessary, attacking your own party or using contextually-useless spells in battle to give yourself an edge goes against RPG convention – so it’s easy to see why it’d be offputting: it's unusual, takes a lot of particular adaptation to squeeze the most out of its systems, and expects you to understand those systems to stay ahead of the curve.

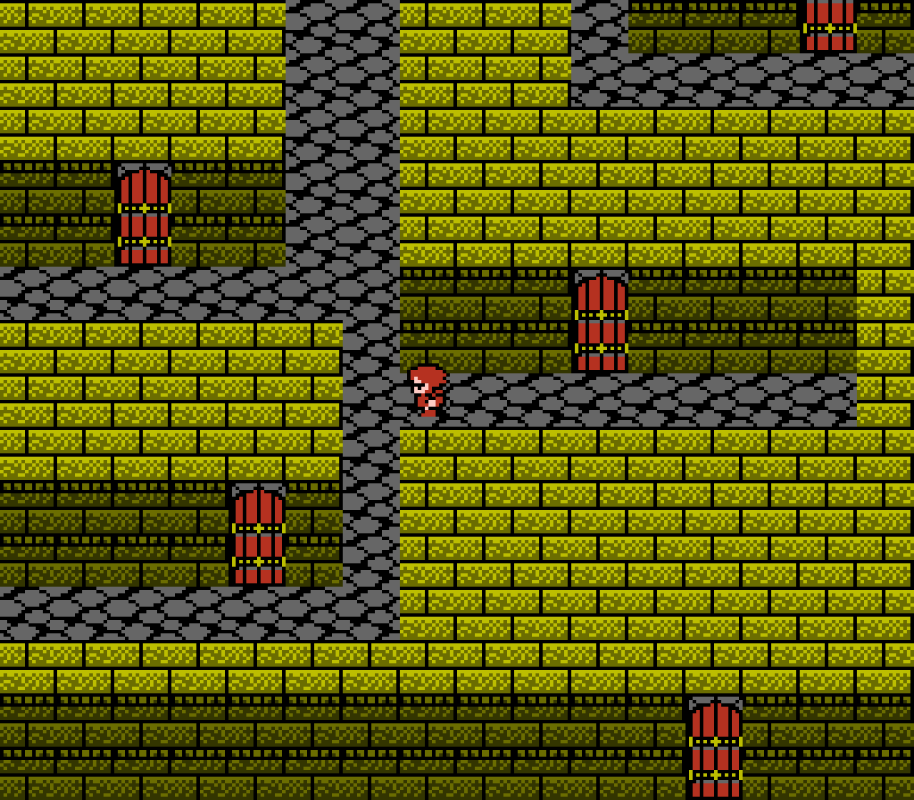

Though the growth system and all its oddities aren’t the only thing distinguishing the game from most other Final Fantasy titles: as a whole, it’s far closer in structure and appeal to the dungeon-crawlers of its era than it is to the later games in the series! It’s a slow, combat-focused numbers-game that aims to stay compelling through forcing smart problem-solving and resource-management over the course of a multitude of battles, where the depth of the combat comes from its subtleties: smart and deliberate attack placement through understanding the health and threat level of each enemy type, and taking advantage of enemy rows to mitigate damage where needed. It’s a game where you’ll spend upwards of an hour in each dungeon, risking complete loss of progress if you get careless or run low on resources, and expects the character progression gained from clearing it and the relief of success to be the sole motivators to keep on going. But by virtue of wearing the title of an incredibly popular, long-running series, it’s more likely to be played by a fan of the series’ future looking backwards out of curiosity than by someone who’s drawn to the genre-space it resides in; a fan whose love for the series was stoked by games without attritional labyrinthine dungeons or classically-simple combat systems, and with a larger narrative focus as a motivator to push through any pain points they have with the gameplay – someone who’s likely to wind up having a rough time with the game, be it for struggling to adapt to the game’s structure and idiosyncrasies, or simply not liking it for what it is.

And someone who’s struggling with a game, or isn’t enjoying it but hasn’t committed to dropping it, might consider leaning on a guide to push through. Guide use – which, anecdotally, feels very normalised for games of this era – meaningfully affects the balance of these classic RPGs in a way that’s easy to overlook, and likely to the guide-user’s detriment: in short, it’ll literally make them weaker! Directions and dungeon maps effectively minimise the steps the player takes – and by extension, the enemies they fight – and a game with vague instructions for progression combined with an open-ended world and mazelike dungeons (including this game’s signature pick-a-door trap rooms) clearly isn’t balanced around the person who can navigate them perfectly; the unknowing player will fight far more encounters while running around, and thus become meaningfully stronger than the person who knows exactly where to go. And that’s an extra factor to consider when feeling forced to grind, in a game that has a reputation for its grinding; though that reputation tends to to get directed towards its leveling system, it’s hard to not think this is at least a contributor for people who wind up using a guide.

So, as I look on at Final Fantasy II’s heavily-maligned reputation, and imagine the vast majority of people playing it are fans of vastly different games within the same series who’ve grown different priorities, preferences, habits and expectations, I can only think that it’s not the fault of the game itself, nor that of the people not liking it, but simply that it’s landed with the wrong audience. Not that it’s a very broad audience, of course – it *is* still an ‘80s dungeon crawler, with all the baggage that carries! – but within that niche, I think it’s a wonderful game.

~*ʚїɞ*~

Thank you for reading! This is by far my biggest and most ambitious piece of writing I’ve put out in a very long time and the first I've decided to share outside of my usual comfort zone; it's been a bit of an ordeal, but I’m glad to have been able to dedicate it to a game that’s quickly become something special to me. Even if I can't convince you to give the "enemies with a petrification chance on their basic attacks" game a go, I hope I can at least reason why "bad" video games aren't necessarily, well, bad.

If you'd like to support my efforts elsewhere, please give this same post some attention over on Substack, or even subscribe if receiving these posts via email sounds a bit more convenient than this (it's free, and it'll always be). See you next time!