Wordless Storytelling in Subterranean Animism

Touhou games are the most beautiful games ever made, we already know this; using every element of their play – visuals, audio, the bullet patterns and the movements you have to make to dodge them – to wordlessly convey character and mood through the act of shooting and dodging. It’s the games’ aesthetic beauty only being complete through your own actions, the artistry of your movements that each pattern forces; a duet where your partner is the game itself. It’s the feel of fighting and crashing your way up a harsh waterfall, to be eventually met with the relief of breaking through to the peak; or of soaring up into the sky, pushing through the unknown, and piercing the clouds. And if each game collages these beautiful individual moments to express its thematic identity – Perfect Cherry Blossom’s restrained solemnity, Imperishable Night’s pomp and bombast, Mountain of Faith’s meeting of nature and mysticism – then Subterranean Animism’s, if anything, is one unlike any other in the series: adversity.

Its clearest means of expression is through its difficulty, being much harder than most others in the series and ramping up much quicker as well; rather than having the typical Stage 4 Difficulty Spike, it demands genuine respect as early as Stage 2, and continues to climb steadily from there. Beyond their straightforward density and difficulty, patterns begin to demand much more intricate solutions – heavy redirection, unfocused dodging, manipulating specific gimmicks, to name a few – and the stages' streaming sections start to pile on enough extra noise to become genuinely complicated and difficult. This is all compounded by an extend system that rewards only mastery of the game: clear a boss attack without getting hit and earn a life piece, collect 5 pieces for a life; no resources for scoring, only through perfecting enough boss attacks to keep ahead. This harsh dynamic can be gamed somewhat through bombing, but bombing costs power, and losing shot power increases the time you spend on each attack, increasing the likelihood of getting hit or having to bomb more and spiral even further. The Former Hell stands out as such a dangerous place within the series’ world because it’s so much more difficult than everything that surrounds it; without that, it wouldn’t carry near as much weight.

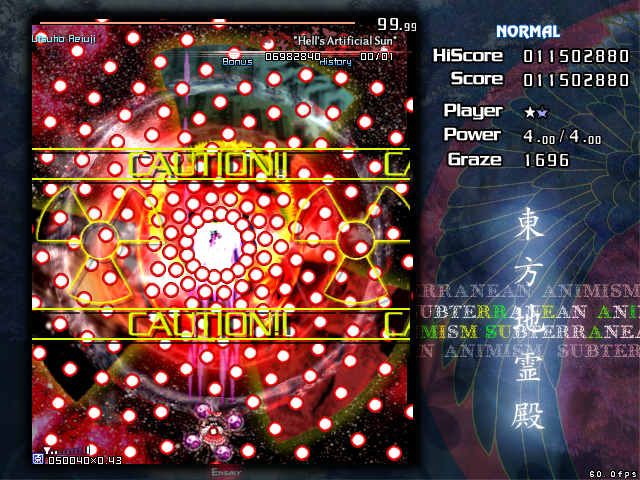

The denizens of the Former Hell and its surrounding areas are hated and unwelcome in Gensokyo, but as they are in your world, so are you in theirs; it’s a fact made as clear as early as Stage 2's Deep Road To Hell, a music track and boss patterns so unusual to the series as to feel alien, and only gets more and more intense as you descend further towards the Blazing Hell. Stages flood the screen with bullets and massively restrict your movement, aimed bullets become intensely fast and more frequent as to feel like it just wants you dead, and the stage patterns and backgrounds slowly forego their usual beauty for simple, intense challenge backed by increasingly-prominent hellfire. It culminates in a finale where all of music, background and spell visuals feel like a direct assault on the player – the mid-boss’s attack is harder to look at than it is to dodge! – and the final boss’s spells are such a sensory assault on the eyes and ears that they start to become genuinely hard to parse by the end. Touhou dials back its signature beauty and replaces it with threat, with adversity; you shouldn’t be here, you don’t belong here, why are you persisting?

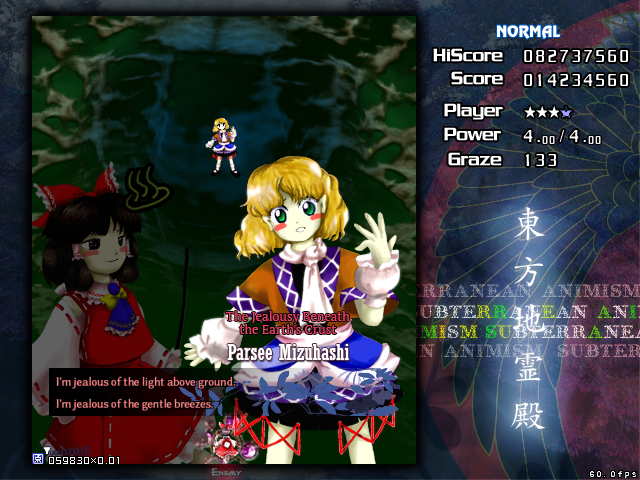

The Former Hell is clearly a desolate place, and carries that heavily through its striking difficulty and through both fiercer and more melancholic presentation compared to other locations in the series – but it isn’t all struggle and adversity; it’s a much broader, often more positive, range of emotion, carried through music just as much as the dialogue itself. Parsee’s quiet, resigned jealousy is immediately contrasted by the loud, busy streets of the Former Hell and of Yuugi herself, and the danger of the first descent into the Blazing Hell is punctuated not by fear or aggression, but a calming lullaby and a caretaker carrying herself with cheer – before suddenly blowing into its crescendo at the turn of its final act. The pure sound of the game feels that of a world that’s collapsing around its people – those rejected and reviled by the outside world, and forced into a dying, abandoned hell – and a reflection of the ways they're able to come to terms with their situation. Those forced out of society, having been hated into dire circumstances far out of everyone else’s sight, and being forced to make the most of it – whether they’re able to, or not.

As much as I love these games, Subterranean Animism has been the first and only to tease so much genuine curiosity and imagination towards the story and setting of the game, and a game that manages to do so purely through the language of the arcade was never not going to be something exceptionally special to me. Wonderful game, I hope I can beat it some day.

~*ʚїɞ*~

Thank you for reading, as always. Firstly… I spend a lot of time describing musical significance sort of abstractly in a way that probably won't make much sense if you aren't familiar with the game to begin with, and I also didn't want to flood the piece with so many out-of-context track links that keep interrupting the writing itself!, so I'd maybe suggest watching (or even playing…) the game in full if you want to understand that a little bit better. Anyway…

Touhou has very quickly become one of my favourite things ever – anyone remotely close to me knows this! – and I really wanted to put out a strong piece to try to convey that. And Subterranean Animism, in particular, has quickly become the most interesting one to me: while the series is fantastic at conveying particular moods and feelings, this one feels like its aesthetics carry a unique amount of narrative weight – I realised at one point while playing that I was coming up with very particular ideas about the game’s world and its situation, without really knowing what was actually happening in the story! And the difficulty of it sells it in a way that simply wouldn’t land if it were similar to the typical Touhou fare; I think games like this really cement my feelings on the importance of difficulty in games as a means of language and expression, which… might not be the most popular so soon after Silksong brought out another wave of Difficulty Discourse. Oops! I think I’d like to write about that in more detail some day.

If you'd like to support my efforts elsewhere, please give this same post some attention over on Substack, or even subscribe if receiving these posts via email sounds a bit more convenient than this (it's free, and it'll always be). See you next time. ~♡