MOTHER and Childhood Through Play

I think it’s important to get this out of the way, especially considering its reputation in wider circles, but MOTHER isn’t a particularly difficult game when put next to its contemporaries. It’s maybe so to an extreme, sometimes: it’s effectively classic Dragon Quest but with very little consequence for dying, where enemies don’t demand much more than mashing the attack button for a long stretch of the game, and whose dungeon layouts, overworld navigation and puzzle-solving are all much more straightforward than they appear. It never really comes close to the same level of challenge or satisfaction as a solid dungeon crawler from the same era, while still existing in that same genre space that, to me, needs that tight resource-management and decision-making that this game comparatively lacks, in order for its immediacy to stay engaging.

And yet, I’ve fallen absolutely in love with this game the second time around, said love being spurred on through a small detail in an early sequence: after running about for a few hours swinging sticks at the local wildlife and anything else he can see, Ninten is sucked into a fairytale fantasy world of fairies, castles and magic. And upon descending into this dreamland’s dungeon, he finds a sword… that he can’t use, and a dragon… that doesn’t so much as acknowledge him, right before he’s drawn back out into reality. That moment contextualised the rest of the game for me, the whole game being an expression of a child playing pretend: Ninten really believing that he is the Dragon Quest hero swinging swords and slaying monsters, when in reality he’s a kid running around, meeting other kids, learning to sing, and poking his nose in places he prooobably shouldn’t be. That playful imagination befits USA urban fantasy being relayed largely through fighting zombies and aliens: do they really exist in this world, or is he just imagining himself fighting what he’s seen on TV? And it then becomes very fitting that the more immediately meticulous or irritating aspects of the experience are not the make-believe fantastical, but the real-world mundane; asthma attacks, catching other people’s colds, or even just the physical process of managing items and money.

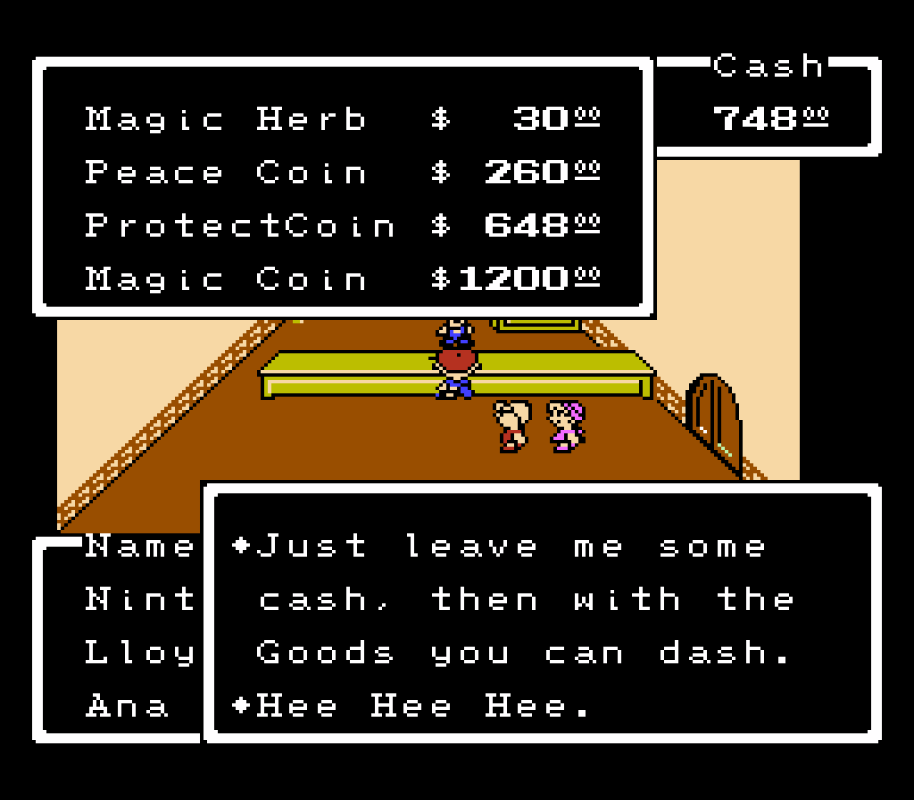

So, of course the combat is going to be easy if it's a group of kids playing pretend! The most interesting way that low difficulty presents is not through a lack of immediate challenge from enemies and dungeons (which are mostly straightforward, but ramp quite hard into ‘genuinely challenging’ territory by the end), but from how much of a safety net the game lends you at all times. As touched on before, there’s practically no punishment for dying – only money on your person is lost, whereas all money won from combat goes directly into your bank account – and, once Magicant is unlocked, you can warp at any time back to the magical fantasy fairyland with no danger and where you can save and heal for free, and have access to most of the game’s services and conveniences in a single hub. And when the combat difficulty does pick up, its mechanical identity becomes that of identifying which enemies are the most threatening and least worth fighting, and running away from them. This paradigm shift happens around the time when Ninten has been cleanly outshone by his friends in either physical or psychic power – and his strongest asset becomes his ability to run away from enemies with no risk of failure. Between being able to escape from enemies risk-free, and being able to escape back into Magicant to safely recover whenever needed, the game being built around running away from danger feels very apt for a group of kids playing around in dangerous places; the danger being exciting, but the risk and consequence of genuine harm being nothing short of terrifying.

The layout of the world itself expresses that dynamic so strongly, the feel of danger without the actual threat. The journey through this fantasy America feels massive and intimidating; all of the roads and connections between each part of the world are long and winding as if aiming to disorient, yet are all very straightforward and linear in practice. It’s fantastic at guiding you heavily to where you’re supposed to be, but equally so at obfuscating it. The swamp, for example, is a visual nightmare to even look at a map for, weaponises the game’s limited screen size as to feel like you’re stumbling around a nigh-unparseable labyrinth by never letting you see far past your immediate position, and it paths and winds itself in such a way where it always feels like you could be going the wrong way – yet is actually just a linear route forwards with the occasional very short dead end. Similarly, Duncan’s Factory is a giant dungeon with about ten storeys that constantly loop back on each other into dead ends, and has practically no visual distinction between any individual parts of the dungeon, and yet just trying to climb upwards – the exact same approach as in the previous factory – leads very quickly to the end and bypasses most of the misdirection. The massive world suddenly opening up almost-fully after reaching a train station feels vastly overwhelming, but most of those areas only need a surface-level exploration to find their key objectives, and – as with the rest of the game – those objectives are heavily hinted at, if not told to you directly, even when they appear to border on silly or cryptic, just by talking to everybody.

MOTHER feels like the story of a make-believe kids’ adventure in a world much bigger than them: it carries the feel of danger and the excitement that comes with it, but offsets any genuine threat by giving help that feels very gentle rather than overbearing, like being watched over by someone trusted who cares about you and your safety: someone who lets you stumble around and get bruised a little, but not let you the way of genuine harm; and the way the lack of difficulty often manifests through the ease of escaping a tight situation feels like having the security to lean on that person whenever needed. The way a game expresses itself through its difficulty is something that’s incredibly interesting to me at the moment, but in my experience that typically manifests through games using high difficulty to push back against you in really interesting and expressive ways. So, seeing a game wield a similar-feeling level of intent towards making itself easier is deeply fascinating to me – and in doing that, MOTHER twists a very typical RPG structure usually used to tell stories of slaying monsters and evil into an expression of love towards childhood and play.

~*ʚїɞ*~

Thanks for reading, as always. Firstly, I hope the intro paragraph doesn’t feel too much like downplaying to the people who do struggle with the game. I was wary of writing out something like that because it feels a little toxic regardless of context, but literally everything I like about this game does hinge on the fact that it’s easier than, like, every other RPG I’ve played of the same era, so there wasn’t really a way around it this time.

Anyway, MOTHER is a really interesting game to me: I first played it in 2022, and it was the first old RPG I’d played that wasn’t, like, Pokemon, and I had a really good time with it. I wouldn’t play any more classic RPGs for, like, two years, but I’d like to think it softened me up to the idea of them… and now, with so many more of them behind me, the contrast between this game and the rest of its genre space recontextualised it in a way that made me fall very, very deeply in love with it. My truth is that I never really engaged very deeply with any artistic mediums until a few years ago, so I’ve recently been having similar experiences with lots of different things: gaining much wider genre and culture knowledge, and having that swing back on works I’ve liked in the past and helped me appreciate them that much more.

Also, obviously this game is about a lot more than pure childhood whimsy… but trying to discuss everything else as well would have gone way beyond the scope of this thing :p

If you'd like to support my efforts elsewhere, please give this same post some attention over on Substack, or even subscribe if receiving these posts via email sounds a bit more convenient than this (it's free, and it'll always be). See you next time. ~♡